Abstract

This study examines the changing scenario of agricultural education in India within the framework of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 and its capacity to contribute to the goals of Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India). Despite steady growth in enrollment and institutional expansion, India’s agricultural education system faces persistent challenges including gender and regional disparities, quality inconsistencies, and employment concerns. The research analyzes how NEP 2020’s key provisions—promoting multidisciplinary learning, integrating agriculture into mainstream education, emphasizing vocational training, and leveraging technology—can address these issues and transform agricultural education.

The study employs a comprehensive review of current literature, policy documents, and educational statistics to evaluate the alignment between NEP 2020 and the existing agricultural education system. Findings reveal that NEP 2020 offers significant opportunities for systemic reform, including curriculum overhaul, improved accessibility through language inclusivity, enhanced industry-academia collaboration, and a stronger focus on research and innovation.

The research concludes that successful implementation of NEP 2020 can potentially revitalize agricultural education by producing a more skilled, innovative, and adaptable workforce. This transformation aligns closely with the goals of Atmanirbhar Bharat, promising enhanced agricultural productivity, innovation in agri-business, promotion of sustainable practices, rural development, and increased global competitiveness. However, realizing this potential requires addressing deep-rooted challenges and perception issues surrounding agricultural careers.

Recommendations include developing standardized curricula, expanding scholarship programs, establishing formal industry partnerships, integrating entrepreneurship courses, and leveraging technology for improved access and quality. By implementing these measures, India can significantly enhance its agricultural education system, contributing to the sector’s growth and sustainability, and advancing towards the vision of a self-reliant nation.

1. Introduction

Agriculture in India is undergoing notable changes and facing several challenges still it plays a significant role in the country’s economy. It holds significance in remaining livelihoods by contributing 18% to India’s GDP as well as employing about 42% of the population as of 2024. For the Financial Year, the Gross Value Added (GVA) of agriculture stood at $275 billion. Marking a notable increase from past years, the agricultural exports reached $53 billion (Press Information Bureau, 2024; Economic Survey 2023-24).

In accordance with ASER (Annual Status of Education) – 2018 report, since 2010, the percentage of children aged 6-14 years enrolled in schools has been rising at over 96% annually. The Right to Education Act 2009 provides that all children between ages 6 to 14 must be given opportunities for acquiring free compulsory education. Even though there are worries regarding school instructional quality, reach has improved. Moreover, higher education is paramount to national development by enhancing early development and equipping adolescents for meaningful societal contributions.

The production, processing, distribution, and consumption of food would all need to drastically change if the world’s population of roughly 10 billion people is to be fed by 2050. To feed the growing population and to guarantee decent employment and livelihoods for producers and actors, improvements at the global, regional, and local levels of the food systems are required (FAO, 2021; Woodhill, 2022). There is a great deal of promise in agricultural research, policy support, and institutional innovations to transform agriculture and feed the world’s population in the future and end hunger.

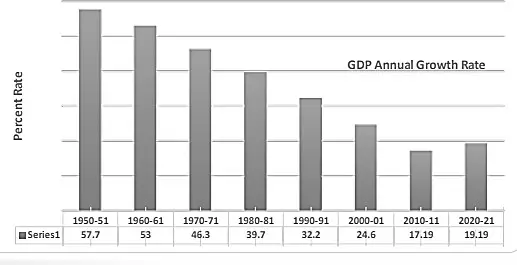

In the 1950s, the agricultural sector made up 56.70% of India’s GDP; however, after that, its share has declined and as of 2020-21, it now only makes up 19.19% (Figure 1), (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementations, MOSPI). But as economies grow, it is a natural progression for all countries, including India, to move from an agrarian-centric to an industry- and service-oriented economy. However, given that the sector still employs close to 50% of the workforce, agriculture, agribusiness, and agri-based industry in India play a special and strategic role in fostering job creation, ensuring the security of food and nutrition, and fostering broad-based economic development.

Figure 1: Variations in India’s agricultural GDP percentage over time

Source: www.mospi.gov.in

Scientists and planners are concerned about the recent developments in Indian agriculture, which point to a stagnant or declining factor productivity (Chand, 2011). Natural resource depletion, the sluggish pace of new inventions, and human resource shortages are a few of the numerous factors contributing to this decline.

One of the major aims of the National Education Policy 2020 is to transform the Indian education system. It emphasizes on agricultural education so that the productivity and sustainability of the agricultural sector can be improved. NEP 2020 provided a thorough explanation of how education should be approached holistically, from early childhood to higher education (NAAS, 2021).

The concept of integrating agricultural education into the mainstream curriculum has its origins in the historical importance of agriculture in India and the necessity to modernize and enhance agricultural practices. By incorporating agricultural education into the NEP 2020, the aim is to promote sustainable agricultural practices, enhance rural livelihoods, and contribute to the overall development of the agricultural sector in India (Agrawal, 2024).

The Indian government has launched ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (Self-reliant India) to move towards a self-sufficient economy (Rathi, 2021). The agriculture sector is a very important sector for a developing country like India. Through this sector the concept of self reliance can be achieved. Atmanirbhar, a term in Hindi meaning self-reliance, was first introduced by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 1998. The mission aims for preparing India for the global market as well as promoting manpower skills and reducing the dependence on other countries. For instance, the Government of India implemented the National Education Policy in the year of 2020 to reform the educational structure and skill development focusing to make India a self-reliant country which will lead towards a vision of a developed country.

Several schemes have been implemented to uplift the productivity of agriculture. The new scheme called Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY) has been included for efficient irrigation (Wani et al., 2016). Along with PMKSY, for fertilizer usage, Soil Health Card; promotion of organic farming, enhancement crop yields and reduction in input costs are included.

The Indian govt. is promoting many Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) for assisting small and marginal farmers to reduce costs, increase productivity, and to access better markets. New reforms such as the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce Ordinance, 2020, aim for enhancement of farmers’ freedom, so that they can sell their produce and enter into the arrangements of contract farming.

Sustainable practices like bee-keeping, agro-forestry, crop-sericulture, fish farming etc. are promoted by The National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) with special emphasis on enhancement of agricultural productivity in rainfed areas. Also, through Rashtriya Gokul Mission, animal husbandry and dairy farming, the concept of self-reliance is promoted (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Govt. of India).

Thus, it can be stated that by focusing on sectors like agriculture, productivity enhancement, value addition promotion, empowerment of farmers, the vision of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ can be achieved significantly.

2. Literature Review

India’s New Education Policy-2020 aims to strengthen agricultural education by developing professionals with local, traditional, and emerging knowledge. A roadmap and Implementation Strategy for NEP-2020 in the Agricultural Education System was released in September 2021 (Agrawal, 2022).

The study explores the holistic and multidisciplinary approach of NEP 2020 in India’s education system, emphasizing its importance for children’s development and the global education system’s relevance. It analyzes previous policies and literature to convey the philosophy of education (Roy, 2022).

The New Education Policy 2020 in India aims for national integration and economic growth by revolutionizing the educational system. It reorganizes agricultural education, introduces academic credit banks, and advocates for experiential education. Challenges include ensuring access to experiential learning and addressing multidisciplinary education. The policy also promotes agricultural skills and HEIs as global study destinations. (Kumar et al., 2022).

India’s New Education Policy 2020 aims to overhaul the higher education system, focusing on transforming agricultural education and strengthening linkages between agriculture and other disciplines. The policy aims to grow the country’s agricultural sector, strengthen rural infrastructure, and promote value addition. Open distance learning (ODL) can play a role in implementing the Skill Development Mission, enhancing productivity and profitability of small farms. The policy also seeks to create employment in rural areas and secure a fair standard of living (Sreenivasareddy et al., 2021).

India is one of the youngest countries economically superpower with Sixty Two percent of the population aged between 15-59. The country is focusing on the enhancement of its educational institutions through National Education Policy 2020 and the National Research Foundation which will eventually create various scopes of employability (Tippa & Mane, 2023).

According to Gupta & Gupta (2022), Institutions should adopt heutagogy in higher education to foster dynamic learning environments, promoting self-determined learning. This shift aligns with NEP 2020 provisions, preparing students for lifelong learning and promoting effective implementation by educational leaders and faculty.

Jha et al. (2020) critique the New Education Policy, 2020, India’s third in a series, highlighting its drawbacks and addressing global education quality, equality, and private player participation.

2.1 Objectives

- To analyze the current state of agricultural education in India, including enrollment trends, gender diversity, and regional disparities.

- To evaluate the alignment between the National Education Policy 2020 and the existing agricultural education system in India.

- To analyze the implications of NEP 2020 on agricultural research and innovation, particularly in the context of achieving self-reliance (Atmanirbhar Bharat).

- To identify the key challenges and opportunities in integrating agricultural education into the mainstream curriculum as proposed by NEP 2020.

- To explore strategies for enhancing industry-academia collaboration in agricultural education to promote entrepreneurship and employability.

3. Discussion

3.1 Growth of Indian Agriculture

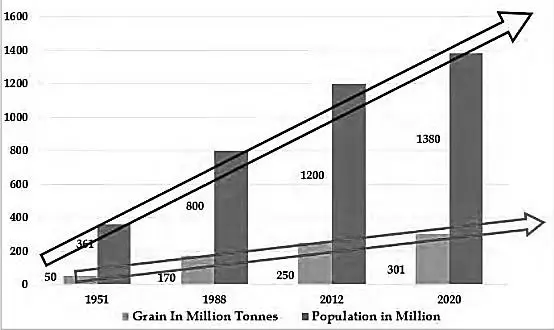

Over 5,000 years of agricultural development in India has established a strong foundation for traditional farming systems, such as the cereal-legume rotation system. Organized agricultural research was initiated with the establishment of camel and ox-breeding farms in 1829, agricultural colleges and research stations in 1868, bacteriological research laboratories in Poona in 1889, and the Imperial Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) in 1905. IARI started building trained human resources, but capacity building for Agricultural Research, Education and Extension (AGREE) received limited attention during the pre-independence period. Post-independence, AGREE received greater attention, leading to the ‘Green Revolution’, turning India from a state of acute food shortage to a food surplus state.Research input in improving technologies significantly contributed to the significant increase in agricultural production, which helped meet the growing population from 361 million in 1951 to nearly 1380 million in 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Grain production and Human population Growth

Source: ICAR-National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (ICAR-NAARM), 2022

3.2 Higher Education in India

The Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Education, is responsible for educational planning, expansion, and improvement in India’s higher education system. Currently, India offers higher education through State Universities (443), Deemed Universities (126), Central Universities (54) and Private Universities (399), with 383 universities receiving central assistance.

According to AISHE report 2021-22

- The total number of students enrolled in higher education climbed from 3.42 crores in 2014–15 (a 26.5% rise) and 4.14 crores in 2020–21 (an increase of 18.87lakh, 4.6%) to approximately 4.33 crores in 2021–22.

- The count of enrolled students climbed by 2 million in a single year to 43.3 million due to the inclusion of 2,400 institutions for higher education in 2021– 2022. Among these students, undergraduate programs represent 79% whereas postgraduate programs have only 12%.

3.3 Higher Education Enrolment

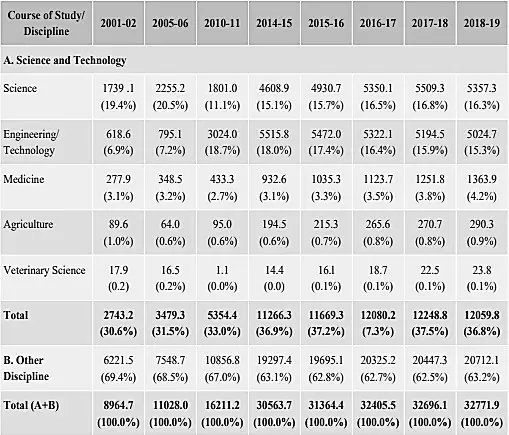

The Indian higher education sector shows a preference for Science, Technology Engineering, Medicine, Agriculture, and Veterinary courses over other disciplines, with a significant positive change in enrolment in engineering (6.9% to 15.3%) and medicine (3.1% to 4.2%) between 2001-02.

Table 1: Discipline -wise enrolment in higher education during 2001-02 to 2018-19 (in 1000)

Source: University Grants Commission (UGC), Annual Reports and AISHE, MHRD Survey reports (Figures in parenthesis indicate percentage to total)(Research and Development Statistics, 2019-20 of DST)

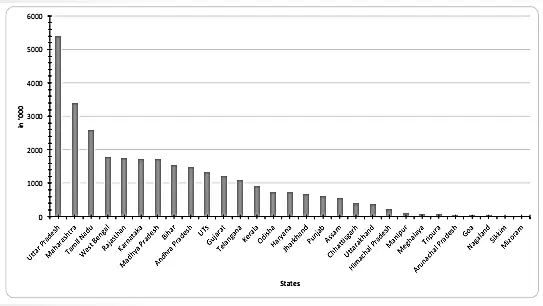

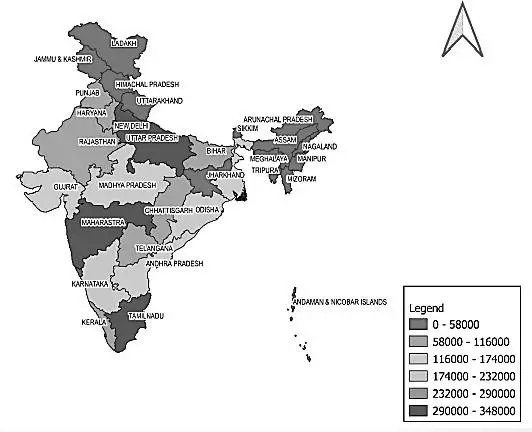

For example, in Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Chhattisgarh, Odisha and North-Eastern states such as Sikkim, Assam, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh, the enrollment in undergraduate programs was very low (less than 9.0 lakhs), whereas it was comparatively high (17.61 to 54.02 lakhs per year) in Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu (Figure 3).

Figure 3: State-wise Enrolment in UG courses

Source: NAARM Report, 2022

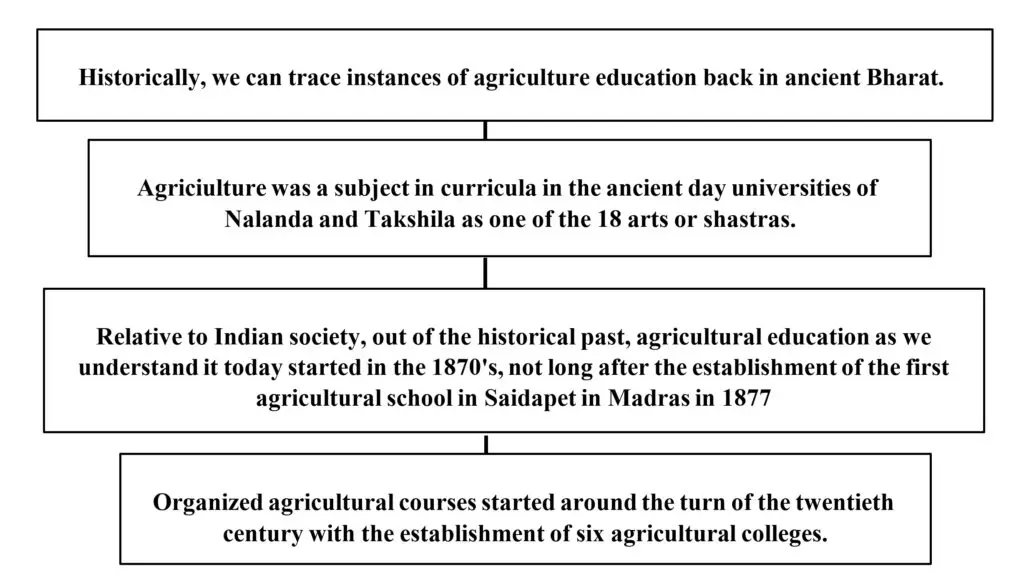

3.5 India’s Agricultural Education Evolution

Agricultural education in India has been around since the Middle Ages when agriculture was one of the major subjects offered by Takshashila and Nalanda Universities (Figure 4). However, formal agricultural education occurred only in the early 1900s, with six agricultural colleges being opened in Kanpur, Lyalpur, Coimbatore and Nagpur during 1905; Pune followed suit in 1907 before Sabour at last established itself in 1908.

Figure 4: Chart on Evolution of Agricultural Education in India

3.5.1 Indian Agriculture: Challenges

Throughout history, agriculture has faced several hurdles, including stagnant productivity, depleting natural resources, biotic and abiotic stresses involved in crop cultivation, poor usage of agro-inputs, poor livelihoods from agricultural practices for small and marginal farmers, poorly functioning regional balance, lack of professionals for agricultural institutions, increasing input costs, transition in food habits, increased post-harvest losses, lack of value addition and processing, fossil fuel crisis, increasing quality competition due to globalization.All these hurdles have created a need for a huge workforce to develop quality human resources which is critical to sustaining, diversifying and unleashing agriculture possibilities which is contingent upon innovation and high-end research. High-tech agriculture can be an option considered, which will require high-end and crowded research. The priority of food security in India has been on the agenda since 1947. The agricultural and allied sectors remained dynamic and grew at nearly ~2.9 per cent per annum from 2014-15 to 2018-19. The situation of women involved in agriculture has increased, and food inflation remained below 2 percent for a consecutive two years.Incidentally, the Agriculture Scientists were the first to draft a Model Act and encourage states to construct exclusive State Agricultural Universities for research and education purposes, which positively impacted food grain production and subsequently ended food imports. Regardless, the situation of food security in India remains alarming, with ranking of 67 out of 81 countries in the level of food security exposing an extremely alarming food security situation.

3.5.2 Agricultural Education: Present Scenario

Agriculture is vital for India’s growth, providing livelihood employment. However, in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, agricultural education is not offered separately, and some states lack academic or financial support, hindering school-level education. Agriculturally-based education is recommended for manpower development.India’s agricultural higher education system, primarily driven by Agricultural Universities (AUs) based on the USA’s Land-Grant model, has led to two successful revolutions: Green and Rainbow Revolutions, focusing on green equipment production, scientific manpower, teacher training, and research for India’s ‘Right-to-Food’ status (NAAS, 2021).

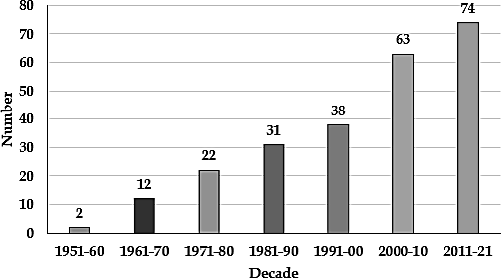

Figure 5: India’s Agricultural Universities’ Growth during 1951–2021

Source: All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE), MHRD (2021)

The graph illustrates a significant pattern of India’s emphasis on agricultural education which is increasing throughout the years. From the beginning in the 1950s with a few agricultural universities, this industry has eventually expanded. A significant increase has been noticed after the year 2000 in this industry. It indicates that a special focus was driven by the Govt. of India as well as educational institutes to improve agricultural education.

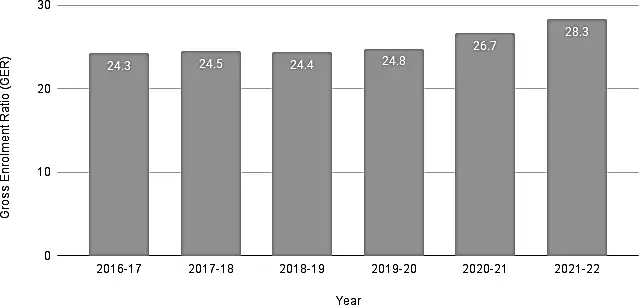

Figure 6: Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in Higher Education for Age Group 18-23 years during (2014-2022)

Source: All India Survey on Higher Education, MHRD (2021-22)

The chart illustrates a steady upward trend in Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) in higher education during the period of 2016-17 to 2021-22. It is noticed that the GER increased to 28.3% in 2021-22 from 24.3% in 2016-17. This growth signifies that an expanding access to higher education in India was mostly driven by several govt. initiatives, changes in different policies.

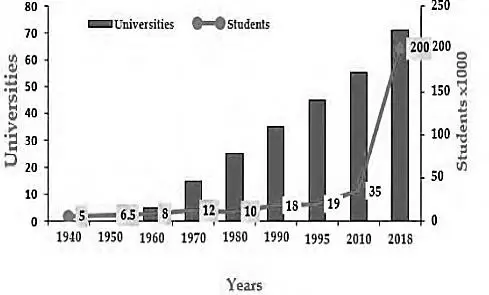

Figure 7: Students intake in Agriculture (1940 – 2018)

Source: ICAR – NAARM Report (2021)

The chart describes “Students Intake in Agriculture (1940–2018)”. The historical overview provides a brief analysis of the growth in agricultural education universities in India with the corresponding increase in student enrollment throughout the years. The data was sourced from the ICAR-NAARM Report (2021) and it shows an important rise in both the number of universities and the student intake over the period of nearly eight decades.In the year of 1940, there were fewer than five universities which used to offer agricultural education. The student intake in the 1960s increased to around 18,000 students. Hence, the trend continued through several decades like in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. The steady growth in universities and student numbers were evident. Between 2010 and 2018, the most substantial growth occurred. A significant expansion was seen in India’s agricultural education. It aims to improve the significant sector and meet the increasing demand for trained professionals.Through the chart we can see the evolving scenario of agricultural education in India. It indicates a consistent effort in capacity building in this sector. Also, it suggests that in case of national development, economic stability and food security, agriculture’s role is very significant. The US Land-Grant system introduced agricultural education in the early 60s, influencing infrastructure, course structure, content, faculty, and practical training. The Indian Council of Agricultural Research supports agricultural education through Central Agricultural Universities, State Agricultural Universities, and Central Universities with Agriculture Faculty.

3.5.3 Diploma Education

Colleges and universities are divided into diploma, degree, postgraduate, and doctorate students. The agriculture and allied sectors require skilled laborers for agro-processing, agrimarketing, and other services. Diploma education is urgently needed, similar to engineering services. In Jammu & Kashmir, Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and northeastern states, diploma courses are available in several State Agricultural Universities. Diploma programs range from two to three years, with a minimum qualification of 10th standard or equivalent.

Figure 8: Enrolment in diploma courses (NAARM, 2022)

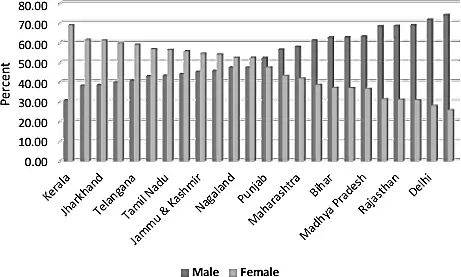

3.5.4 Agricultural Education: Gender Diversity

The agricultural sector today requires more and more involvement of women as is evidenced by the increasing enrollment of female students in various institutions offering courses in this area. In terms of national statistics, ‘44.31%’ of students studying for an undergraduate degree in agriculture education are female while ‘55.69%’ are male. Nevertheless, there are some states (such as those illustrated on the graph such as; Kerala, Jharkhand and Telangana) where the number of girls enrolling is higher than that of boys which means it offers hope for girls who have shown interest in education linked to farming.The growing interest of women in agriculture leads to increased participation, promoting diversity and innovative approaches. Improved gender balance in agricultural education, with higher females studying, promotes inclusion and equality across disciplines.

Figure 9: Gender Equality in Agricultural Education

Source: NAARM, 2022

3.6 Students Perceptions and Career Options on Agricultural Education

A study by ICAR-National Academy of Agricultural Research Management (NAARM) reveals that BSc (Agriculture) is often not on the priority agenda for biology background students after XII class. The study used the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to understand students’ prioritization of bank jobs, government jobs, private jobs, higher studies, and entrepreneurship for achieving a good status in society through livelihood. The top priority was government jobs, followed by higher education, bank jobs, and higher studies. Entrepreneurship and private jobs were the least prioritized, with 10% and 8% weightage respectively. Family circumstances were the top priority, followed by capability and own interest. The study concludes that a government job is the best choice for achieving a good status in society through livelihood. According to Rao et al. (2000), Most secondary school students in India perceive agricultural education as poor and unaffordable, leading to a shift in attitudes and values towards urban classes. This shift is causing a distance from agriculture, which is the root of rural India, and necessitating a positive shift towards rural work.The National Agricultural Innovation Project (NAIP) The demand for agricultural human resources has shifted from the public sector to the private sector, with a 50% gap between demand and supply in sectors like horticulture, dairy, and veterinary. Recommendations include increasing graduates and para-staff, meeting agricultural education needs, and sharing responsibility.

3.6.1 Issues Related with Agricultural Education

There are many issues related to agricultural education in India but few of the issues can be stated such as:

- Deficits in the system

- Access to agricultural education and social class

- Jobs Availability

- The urban nature of agricultural education

- Agriculture education’s fragmentation

The demand for agricultural higher education is driven by job opportunities and cost- effectiveness, but it has weaknesses such as not fully relating to development programs and isolating graduates from farming communities. The merit-based admission process favors urban middle-class students, fragments urban colleges, and varies academic standards, leading to underrepresentation and lack of comprehensive science and policies exposure (NAAS, 2021).

3.7 New Initiatives to Drive More Students in Agricultural Education

India’s government aims to become a ‘knowledge economy’ by prioritizing higher education. The ICAR, with the World Bank’s support, is launching the National Agricultural Higher Education Project (NAHEP) with a cost-sharing of $165 million. The project aims to enhance the relevance and quality of higher agricultural education, improve learning outcomes, foster employability and entrepreneurship, and enhance institutional and system management effectiveness. The project is a 50:50 cost-sharing initiative (NAAS, 2021).

Student READY programme

The Student READY programme, launched by the Indian Prime Minister in 2015, consists of five components: Experiential Learning, Rural Agriculture Work Experience, In Plant Training/Industrial Attachment, Hands-on Training/Skill Development Training, and Student projects. Funded by ICAR, it aims to enhance agricultural graduates’ capabilities in handling field and industry problems.The lack of talented students in agricultural science and technology is a major constraint for India’s farm prosperity and growth. Students often prefer medicine, engineering, and management over agriculture. Thus, multipronged strategies should be adopted at school boards/university level, government level, and policy options to attract the best talent.

a) Academic Environment in Agriculture: It emphasizes the need for changes in university education, including teaching methodologies, curriculum development, faculty competency enhancement, campus placement arrangements, and budget allocation, while aligning agricultural education with National Education Policy philosophy.

b) The integration of agriculture into the school curriculum: The National Educational Policy (NEP-2020) suggests integrating agriculture into the school curriculum, promoting a multidisciplinary approach across sciences, social sciences, arts, humanities, and sports. This approach aligns with all levels of education, from primary to higher education, and encourages young people to consider agriculture as a potential career.

c) Agricultural education beyond NARES: The National Agricultural Research Education System (NARES) is primarily responsible for agricultural higher education, with courses on agriculture and allied sciences required in General/Central Universities under the National Education Policy-2020.

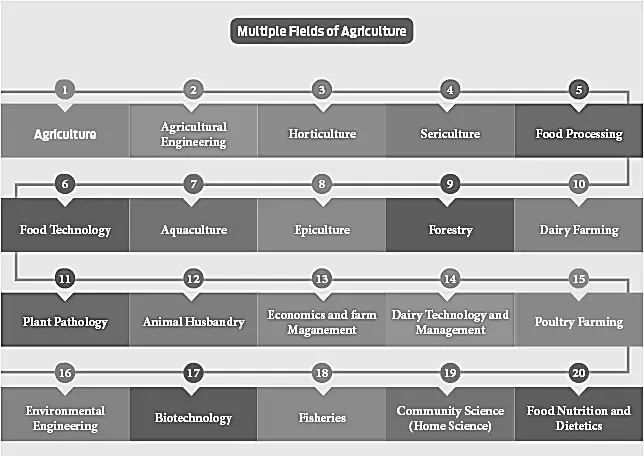

There are huge scopes from the Government perspective. Farming is often seen as a laborious and unprofitable vocation, but it can be a promising career option for youth. To improve the sectoral image, greater awareness of its benefits, market engagement opportunities, and innovations in the agriculture sector should be created. Utilizing print, electronic, and social media to connect successful entrepreneurs and influential personalities with the community is crucial. A national-level strategy should provide support to meet tuition fees for meritorious and marginalized sections, reducing the rural urban divide and improving the Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER). Agriculture courses in India are offered across a broad range of branches/ specializations. Some popular agriculture courses for Under-Graduates in India are:

Figure 10: Multiple Fields of Agriculture

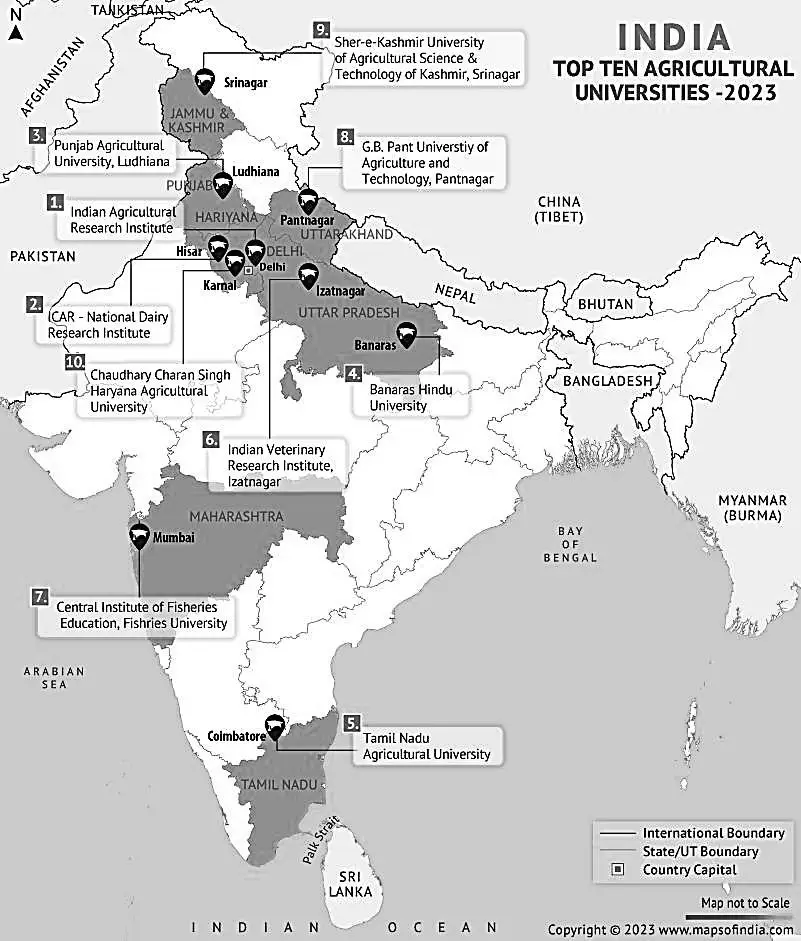

According to Maps of India (2023), top Ten Agricultural Universities are as follows:

- Indian Agricultural Research Institute

- ICAR – National Dairy Research Institute

- Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana

- Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi

- Tamil Nadu Agricultural University

- Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Izatnagar

- Central Institute of Fisheries Education, Fisheries University

- G.B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Patnagar

- Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agriculture Science & Technology of Kashmir, Srinagar

- Chaudhary Charan Singh Haryana Agricultural University

Figure 11: Top Ten Agricultural Universities in India

Source: Maps of India (2023)

3.8 Possibilities in Agricultural Education in India

The Agricultural Universities have developed approximately 400 virtual classrooms and e- courses for their UG programs. These are backed by a centralized Academic Management System, and the recently released ‘Krishi Megh’ will provide additional support for online classes. Post-graduate courses in all areas of agricultural education are being turned into online courses. The NEP suggests a four-year Bachelor’s degree program with multidisciplinary instruction as a recommended option (Times of India, 2020). Students’ top preference in case of academic choice is not a B.Sc. in agricultural education because they don’t have proper knowledge of the field. Conventional employment opportunities encompass government agencies, academic institutions, nationalized banks, and businesses providing agricultural inputs. Agribusiness, food processing, finance, retail, international trade, rural credit and insurance, warehousing and commodities, NGOs, and KPOs are examples of developing industries. Almost half of agricultural professionals are employed in business-related positions. Agricultural marketing, agricultural pricing, agricultural law, agricultural trading and merchandising, agricultural economics, agricultural data analysis, and farm management are the main areas of study for an MBA in agribusiness.Every year, the Indian Council of Agriculture (ICAR) uses the All India Entrance Examination for Admission to give over 4,500 scholarships to worthy candidates. It is recommended for rural students from rural India who have a keen interest in agriculture to pursue careers in agriculture and related disciplines. Every year, the ICAR accepts over 250 international students from more than 20 countries into a variety of degree programs. There are numerous fellowships and initiatives in place to help pay for their further study in India. The NEP seeks to restore India’s standing as a Viswa Guru and promote higher education institutions as major international study destinations.To attract talent, the system should make agriculture education more attractive, earning, and reputed for youths. Enhancing government funding and scholarships based on student merit can attract more students. Proactive policies to encourage the private sector in agricultural education are needed to address the demand supply gap and ensure quality outcomes.

4. Conclusion

India’s agricultural education system has fallen into significant difficulties. This sector is facing both constraints and possibilities. It has been found that there is a positive increase in the case of enrollment and expansion of educational institutions but there are many issues still persist such as regions and gender disparities, inconsistency in quality as well as high concern related with employability. NEP 2020 offers a robust opportunity to reshape agricultural education. For the reshaping, promotion of multidisciplinary learning, integration of agriculture with the prime stream of education as well as integration of technology for improving access and quality of education is required.

Emphasis is placed on real-life experience through programs like Student READY. Thus, the limelight on emerging areas allied with agriculture state that agricultural education is way more relevant, important and attractive to students. Though, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive approach in the system for addressing the issues related with perception to pursue a career in agriculture. It is also necessary to match education with the evolving demands of the sector and the larger goals of Atmanirbhar Bharat.

4.1 Recommendations

By implementing these recommendations, India can significantly improve its agricultural education system, making it more aligned with the goals of NEP 2020 and the vision of Atmanirbhar Bharat. This will not only attract more talented students to the field but also contribute to the overall growth and sustainability of the agricultural sector in India. The recommendations are as follows:

- Curriculum Reform: NEP 2020 mandates a multidisciplinary approach in agricultural education, incorporating technology, business, and environmental studies, and establishing standardized curricula across agricultural universities for consistent quality education.

- Improve Accessibility: Increase accessibility for rural students by introducing diploma courses in local languages and expanding scholarship programs and financial support for marginalized sections and rural areas.

- Enhance Industry-Academia Collaboration: Partner with agribusinesses and food processing industries to offer internships and practical training, and involve industry experts in curriculum development to meet market needs.

- Promote Entrepreneurship: The proposed strategy involves integrating entrepreneurship courses into agricultural education programs and establishing incubation centers in agricultural universities to support student startups.

- Leverage Technology: The focus is on enhancing the integration of e-learning platforms and virtual classrooms, as well as incorporating training on emerging technologies like precision agriculture and IoT.

- Awareness and Outreach: The initiative involves launching nationwide campaigns to promote agriculture as a viable and rewarding career option, as well as organizing agriculture-focused career fairs and workshops in schools.

- Research and Innovation: Increase university funding for agricultural research, encourage student participation, and establish centers of excellence in emerging areas like sustainable agriculture, climate-resilient farming, and agri-tech.

- Policy Implementation: Create a comprehensive plan to execute NEP 2020 recommendations in agricultural education, and establish a systematic system for tracking their progress and impact.

- Skill Development: The initiative aims to introduce skill-based courses and certifications in agriculture and allied sectors, collaborating with the National Skill Development Corporation to align education with national skill requirements.

- International Collaboration: The proposal encourages increased exchange programs and collaborations with international agricultural universities as well as joint research projects to tackle common agricultural issues.

References

Agrawal, R. C., & Jaggi, S. (2024). Transforming Agricultural Education for a Sustainable Future. In Transformation of Agri-Food Systems, 357-369.

Chand, R., Kumar, P., & Kumar, S. (2011). Total factor productivity and contribution of research investment to agricultural growth in India.

Dev, S. M. (2009). Challenges for revival of Indian agriculture. Agricultural Economics Research Review, 22(1), 21-45.

Gupta, B. G., & Gupta, B. L. (2022). Atmanirbhar (self-reliant) Bharat – Heutagogy in Higher Education. Mazedan International Journal of Social Science and Humanities, 3(4), 16-21.

Kumar, K., Prakash, A., & Singh, K. (2021). How National Education Policy 2020 can be a lodestar to transform future generations in India. Journal of Public affairs, 21(3), e2500.

Mukherjee, J. (2015). Hungry Bengal: War, famine and the end of empire. Oxford University Press.

Rathi, M. (2021). Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan: Paving a way of making India Self-reliant. Research Inspiration, 7(I), 04-06.

Shukla, B., Joshi, M., Sujatha, R., Beena, T., & Kumar, H. (2022). Demystifying Approaches of Holistic and Multidisciplinary Education for Diverse Career Opportunities: NEP 2020. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 15(14), 603-607.

Wani, S. P., Anantha, K. H., Garg, K. K., Joshi, P. K., Sohani, G., Mishra, P. K., & Palanisami, K. (2016). Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchai Yojana: Enhancing Impact through Demand Driven Innovations, Research Report IDC-7.

Woodhill, J., Kishore, A., Njuki, J., Jones, K., & Hasnain, S. (2022). Food systems and rural wellbeing: challenges and opportunities. Food Security, 14(5), 1099-1121.

https://factly.in/gross-enrolment-ratio-ger-of-higher-education-improves-but-challenges-remain

https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/54047/1/978-981-19-0763-0.pdf#page=22

https://naas.org.in/Policy%20Papers/policy%2099.pdf

https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2034943

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mahato, S. (2025). New Paradigms of Agricultural Education in the Context of National Education Policy 2020 for Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India). In: VIVIBHA Uttarbanga: Proceedings. North Bengal Publications, India.

Edited by

Dr. Anirban Nandi

Book Title

VIVIBHA Uttarbanga: Proceedings

Copyright information

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to North Bengal Publications : Live Life Happily Org. India 2025

ISBN

978-81-989058-1-9